“My daughters, do not be afraid, this is but a moment and heaven is everlasting”

(Inscription on the icon’s frame)

Maria Teresa Ferragud Roig was born on the 14th of January 1853, in the city of Algemesi (Valencia). Maria Teresa married Vicente Silverio on the 23rd of November 1872, two months prior to her 20th birthday. 9 children were born of this marriage: The eldest daughter, Maria Teresa, a cloistered nun, died before the war; the following two children died in their infancy; the next four became cloistered nuns, 3 in Agullent (Maria Jesus,Veronica and Felicidad), and one in Beniganim (Josefa); one was married, Purificación; and the son became a Capuchin Friar, Friar Serafín.

Maria Teresa was widowed in 1916. In 1936, having been forcibly removed from their convents, the 4 daughters of this family sheltered in their mother’s home, from where they were arrested, along with their mother, who wished, voluntarily, to accompany them through every moment, until the very end of their martyrdom, encouraging them and urging them to remain faithful to their Husband. She was last to die, witnessing the martyrdom of her daughters with admirable fortitude.

This icon has been painted in prayer, following tradition, using the technique of egg tempera and natural pigments, gilded with 22 carat gold. It is a unique piece, n.294.24.

Saint John Paul II, in his “Letter to artists” written in 1999 (n.8) says the following about iconography:

In the East, the art of the icon continued to flourish, obeying theological and aesthetic norms charged with meaning and sustained by the conviction that, in a sense, the icon is a sacrament. By analogy with what occurs in the sacraments, the icon makes present the mystery of the Incarnation in one or other of its aspects.

This might be understood, by analogy with the sacraments, the icon makes present the represented person. The monk A Franquesa explains this calling it “anamnesis”, which allows us to enter a dialogue with the recorded person, a tangible memory, which in some way produces the presence of the person who is recorded.

This is the intention of this icon, to make present in our lives the example and intercession of this holy family.

John Paul II also makes present the term “tradition”, in the Apostolic Letter “Duodecimum Saeculum” written in 1987 (n.12):

Our most authentic tradition, which we share with our Orthodox brethren, teaches us that the language of beauty placed at the service of faith is capable of reaching people’s hearts and making them know from within the One whom we dare to represent in images, Jesus Christ, Son of God made man, “the same yesterday, today and forever” (Heb 13:8).

If we stop to ponder these words, we see that we have also been discussing an art which is also Catholic, preserved by our Orthodox brethren. Which is why we so often look to their icons, writings, tradition and rely on them, since we have shared it at the time when the theology of images was being formed.

The iconographer puts themself at the service of the Church, beyond the inspiration and artistic character of their work, which are also to some degree present in the icon. They rely on a canon established through the councils and tradition of the Church, that painting an image that is a theophany in colours, not to represent the visible world in a realistic way, but instead to show a transfigured image, that makes present the glory of God, it is an access into the mystery of the invisible, made visible through the Incarnation.

For this reason in the icon we do not find ourselves confronted with a photographic or an overly realistic representation, because it seeks an encounter, an encounter which surpasses the vision of this fleeting world, an encounter that is a call to heaven.

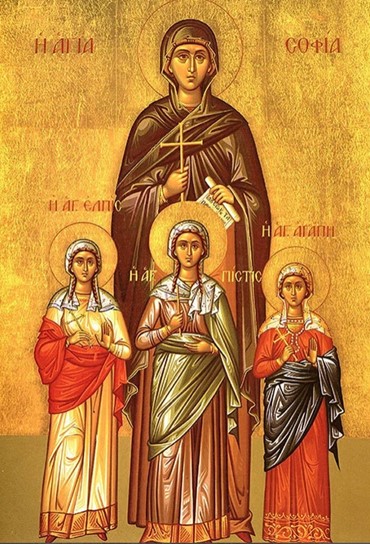

The general image of this icon is based upon the models of the icons of St Sophia, whose daughters Faith, Hope and Charity, were also martyred. In them we see the superior figure of the mother and below her, each of her daughters.

In our icon, María Teresa shows the cross to her daughters, indicating the path to heaven, just as she did in their martyrdom, encouraging her daughters to hand over their lives. She wears simple, austere and soberly coloured clothing. From right to left we see, Sister Felicidad, Sister Veronica and Sister Maria Jesus, wearing the capuchin habit. In one hand they hold the palm of victory and the other hand is held open, as a sign of having confessed the faith. Sister Josefa, shown on the right, makes the same gesture and is distinguished from the others by wearing the Augustinian habit.

The icon has been painted from darkness to light. Following the iconographic tradition in which the painting is layered first with a background of dark colours and little by little lines of light and glazes are added forming the volumes and shapes. This technique differs from chiaroscuro or classical soft blending, to better reflects the light of the Holy Spirit emanating from within. For this reason, there is no focus or light directed from the outside towards the icon. The painting is completed with lively strokes and fine white lines which coat the faces. The garments are also painted using this technique. In a profoundly logical way, their habits have become – through the severity of their often-geometric forms and the lights, in lines and folds – into glorious garments of incorruption. This reminds us that all is renewed and ordered in heaven.

The expression of each of the faces in the icon is contemplative. The colours and shapes have been stripped of age and imperfection to be vested in physical beauty, which is spiritual purity. The icon reflects the divine likeness which man acquires by imitating Christ, the communion between the spiritual and earthly.

Heaven opens to the right of the icon, to pour out its grace. The hand of Christ blesses the martyrs, with the sign of the trinity which is also expressed in three stars.

The gold background breaks the depth of the icon making it a word for all places and all times. In the same way, likewise it breaks the distance between the martyrs and the viewer. It invites contemplation: God unites himself with the praying heart, bridging the distance between it and the painting.

Débora Martínez Muñoz Nicosia (Cyprus), 4th September 2024